Open data: what has changed in the last 4 years

4 years after the Office the Comptroller-General received responsibility for the open data policy of the Brazilian Federal government, the time has come to evaluate what has changed in the period.

How was it in the beginning: from 2010 to 2015

Before that, however, let’s remember a bit about how the open data policy had been conducted until then.

I assumed a public position in 2010 at the then Ministry of Planning, even though it was financially disadvantageous for me, just due to my interest in the theme of open data and the desire to build as a public policy something that was already blossoming in the United States and the United Kingdom, which launched their open data portals in 2009. I was previously involved as a volunteer in several open data projects at the Open Knowledge Foundation, such as CKAN, in which I made the first Portuguese translation still in 2009. CKAN is the free software solution used in those countries’ open data portals and continues to be the most used around the world for open data portals.

The idea that the Brazilian federal government should start to offer open data (which I have told several times (e.g. in 2018 and in 2020)), was incepted in provocation made by Pedro Markun, activist from the Transparência Hacker group, to Cláudio Cavalcanti, then Coordinator-General of Corporate Management at SLTI in the Ministry of Planning, during the Conip 2010 event (someone should archive that video for posterity).

At the time the Open Government Partnership, which promotes social participation in the design of public policies, was being conceived. Moreover, we did not have budget resources available to create an open data portal. So we’ve decided to create everything, from the portal to the very design of the public policy, in the most collaborative and transparent manner possible.

All of the planning meetings and development sprints were open for participation to anyone interested, often taking place out of government premises in places like cafes. They were documented publicly on the internet and whenever possible streamed – and that in 2011, many years before it became a trend for everyone to stream anything – and with one person in charge of bringing voice to the interactions of people online to the physical space of the meetings.

This whole process received a very positive international repercussion. After all, which government project are you aware of, at any point in time, anywhere in the world, that were conducted like this? In this page there is a detailed report of the process. It’s in Portuguese, but there are links near the end to less detailed blog posts in English. Good thing the Web Archive still has an archived copy of the text and images, as the content is no longer available at the original location (more on that unavailability later).

Capacity building, bylaws and scaling: from 2016 to 2017

Despite our success in determining collaboratively what would be necessary to do and in creating an open data portal, the release of open data in public institutions still depended upon convincing individually each authority about the need to sponsor the process. A legal landmark was still missing, something we sought after since the beginning, but until then did not have enough political support to make it happen.

In 2012, the possible thing to do was a bylaw that set forth the National Infrastructure for Open Data – INDA (in the Portuguese acronym) and its Steering Committee. The history of the Steering Committee has already been told in detail in another text in this blog.

However, at the last moments of the Dilma Rousseff government in 2016, came the opportunity to finally enact a decree, as we had been planning since the beginning. That was Decree 8,777, from 11th of May, 2016, which made obligatory in the federal executive branch that each government body or entity would publish open data according to a plan set forth by itself.

However, it was still a challenge to support those hundreds of public organizations to build and put to practice those plans. To that end, we have taught almost 1,800 people how to elaborate an Open Data Plan.

The results were evident: the Brazilian Open Data Portal went from 1,167 datasets in 2016, to 6,278 in 2018, which represents an increase of 438% in two years. The amount of public bodies publishing data on the portal in this period went from a few dozen to over a hundred.

The “schism” from digital government: 2018

Until then, all that was being conducted by the then Ministry of Planning, Budget (or Development, in a certain period) and Management. In 2010, in context of the public policies related to data interoperability in the federal government, called e-PING, it was on the then Secretariat for Logistics and Information Technology – SLTI, where the conditions were created to put data and the automated access to data in the spotlight.

In 2018 the Secretariat for Digital Government was created and took the whole structure that was previously oriented toward interoperability in government. The new directives were clear: everyone had to focus either on the digitization of public services, on the government platform for data analysis, so-called GovData, on the internal APIs for government use or on the simplification of the procedures to open up new businesses. In the words of the then-Secretary, any other subject that wasn’t strictly those (for instance, open data, free software and public software) had no place on the new secretariat. All public servants should be working exclusively on those issues that were considered a priority.

Transparency and Open Data

If digital government could no longer be “home” of the open data policy, where should it go, then? The first natural candidate would be the Office of the Comptroller-General – CGU, which, since the enactment of Decree 8,777 in 2016 already filled the role of monitoring and checking bodies and entities of the federal executive branch in regards to compliance with their own Open Data Plans.

The CGU was also responsible for the policy of transparency in the federal government, having inaugurated the Transparency Portal in the year 2004. But aren’t transparency and open data one and the same? If not, what is the difference?

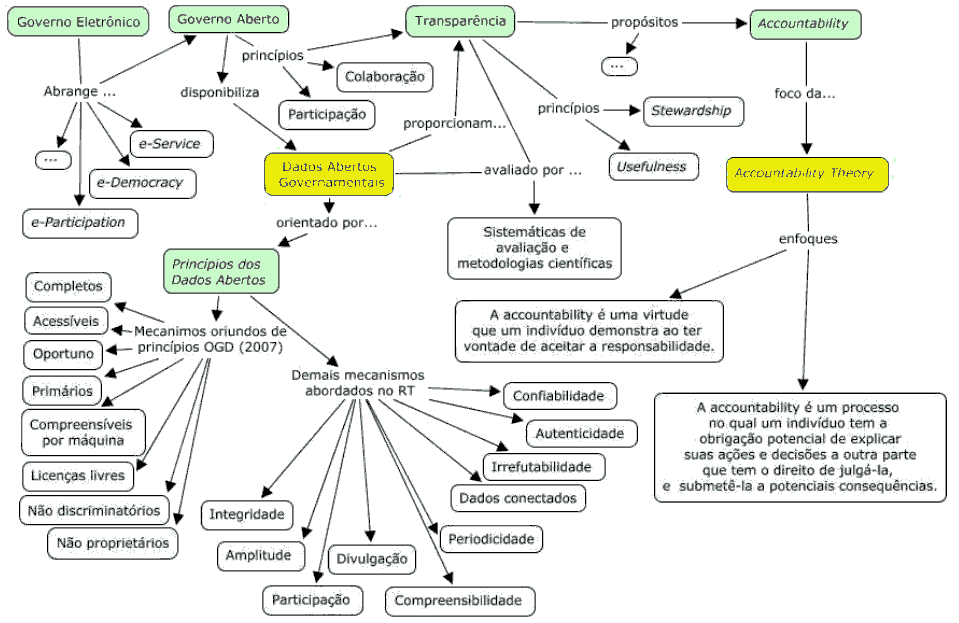

These two concepts share indeed many similarities. Both seek to let the citizen know about something that is produced using public resources, as a form of accountability for using them. They are also a way to reduce the disparity of information resources, and thus power, between the citizen and the State. Opening up data is also a way to give transparency to the inner functions of the State.

However, there are differences in the legal and conceptual origins, in the target audience and in the usage context for the products of those policies.

Transparency comes from the fiscal transparency policy, which in Brazil comes from Complementary Laws no. 101, from year 2000, and no. 131, from 2009, which made it obligatory for all branches and federated entities (Union, States, Federal District and Municipalities) to have their own transparency portal and publish there all income, expenses, budget, procurement, etc. That means that fiscal transparency is closely tied to the direct use of public funds and has a focus on financial values.

It goes without saying that transparency in a broad sense also covers what one does and not only how much one spends in the public sector. However, in practice, that kind of information it is quite less often present in the transparency portals of public bodies, probably because such requirements are not explicitly present in text of the law.

For example, the register of expenses is nominally cited both in LC 101 (art. 48-A, II), and in the Access to Information Law – LAI (art. 8th, § 1st, III). However, data that is a little bit more specific, such as the addresses and geolocation of all schools and health facilities, is not mentioned explicitly in any law.

Transparency usually has for a target audience the “average” citizen, the layman, which has no data literacy. That means presenting ready-made analyses, pre-conceived graphical elements, without many options or conditions to conduct their own analyses or combine data with data from other sources.

With the substantial increase in volume of data used by the public administration in the last decade, it has become ever more necessary to make it possible for the citizen themselves to obtain dta and make their own analyses. The transformations in society, ever more digital, have also changed what the “average” citizen means, as it has become ever more common that people of varied professions have acquired the minimum abilities to work directly with data.

From that comes the need for “open data”, that empowers citizens to make their own use of data as they see fit, instead of being “patronized” by data publishers with ready-made analyses and receiving text documents in PDF format, which make difficult even the simple task of summing the values in a column in a table. It’s also about having independence and autonomy.

Making open data available in a regular and reliable manner also supports a whole ecosystem of digital services that have them in account as a fundamental input. Among many other applications, artificial intelligence systems can use the data to train their models, for instance. Many studies have shown the economic impact of the availability of open data and its role in growing the gross domestic product and in sustainable development of nations.

As opposed to states and larger municipalities, it is still extremely common today, especially on smaller municipalities, to find transparency portals that do not offer open data. They have only data about income, expenses and procurement, often only available in PDF documents.

The LAI has brought, back in 2011, in art. 8th, the requirement to open up data, even though it has not used the term “open data” explicitly. Later the Digital Government Law (Law no. 14,129/2021) has brought even further detailed requirements of active transparency in article 21.

One could say that, from a conceptual standpoint, “open data” is usually associated with transparency, but is also an answer to existing gaps in the practices that have been observed up until now. In the same vein, one can also notice that the legal references of open data come approximately a decade after the legal references of transparency. The concept of open data is also not restricted to the fiscal and financial domain: open data is about everything and any domain of knowledge that an organization might delve into. Where one speaks about open date, it’s common to see very specific data about the operation of a specific public policy, such as, for instance, the time series of fuel prices.

One can conclude from this comparison that transparency and open data are concepts that go hand in hand and complement themselves in many aspects, but are definitely not the same thing. However, thinking of open data simply as one more way to reach the goal of transparency means to limit its potential. Especially the potential towards fostering the digital economy.

The transition

With that, I received orders at the end of 2018 to prepare a transition so that the CGU would take on the responsibility for the open data policy in the federal executive branch, in place of the Ministry of Economy and its Secretariat for Digital Government. That process has culminated in Decree no. 9,903, of 2019. The Brazilian Open Data Portal and INDA, with its Steering Committee went also to the CGU, and the Ministry of Economy kept only a seat at the committee, with a participation role similar to many other ministries.

The last 4 years

Since receiving responsibility for the open data policy, the team at CGU has seen successive changes in management. The INDA Steering Committee has been meeting with increasingly sparse frequency. They have changed the bylaw that, until then, defined the interval as bi-monthly to become only every four months. Albeit they did not comply with even this reduced periodicity: in those 4 years, the committee has assembled only 5 times. In 2022, there has been a single meeting, in May.

INDA’s activities are oriented by an Action Plan. CGU has elaborated an Action Plan for the period 2021-2022. However, according to the monitoring by Open Knowledge Brasil, this plan has seen successive delays and postponements.

As for the Brazilian Open Data Portal, CGU has contracted, in 2021, with the support of Unesco, a restructuring for it. The portal is already online, but problems have accumulated in it. Among them, the loss of memory of historical content, such as FAQs and explanatory pages for the concepts of datasets and open data, and also the whole wiki which archived historical registries of how INDA had operated up until 2018. There is also difficulty with the new interface in finding the data you seek, considering that the search filters are not easily found. Worst of all is the unavailability of the CKAN API, which many organizations used to update automatically their data, including the Ministry of Economy itself.

Even before this renovation, another important integration had already been broken. Before going to CGU, the portal had been integrated with the ombudsmanship system of the federal government. Any time anyone found a problem with a dataset, they could send a complaint that would travel through the ombudsmanship system (initially through the system called e-Ouv, which later became Fala.br). The complaint went along with, in addition to a description of the problem, the URL of the dataset that was the object of the complaint. This would improve resolution, making it an easier job to the person responsible for answering the complaint. In 2020 this integration had stopped working. No explanation was given for the removal of this feature.

To make it worse, all of the thousands of links to datasets that existed before the portal renovation have become immediately broken. No URL redirect whatsoever was created pointing to the new URLs, as is so common in any portal renovation in government (and unfortunately initiatives such as the Web Archive do not always manage to archive the totality of the old content).

One of the few positive changes is the possibility for anyone to log in with their gov.br account (an account that Brazilian citizens must create in order to access any digital services in the federal government) and write comments about each specific dataset (for instance, in less than a week one can already see a whole discussion around data quality problems or corrupt data on the CNPJ company register dataset published by the Federal Reserve). On the other hand, moderating comments in a portal of this magnitude is certainly going to be a big challenge – and that is the main reason that this feature has never been available in previous versions of the portal.

The dissociation between open data and digital government policies have also been criticized by civil society, such as in this article (in Portuguese) by Guilherme Felitti on his Tecnocracia blog, in collaboration with Fernanda Campagnucci, executive director of Open Knowledge Brasil.

Let 2023 come!

This 4 year period has undoubtedly seen few advances and many setbacks for open data in the federal government.

With the new government will probably come new managers, and with them new priorities and new ideas. Maybe in the following weeks we can discuss some of them here and elsewhere.