CNEN and the Return of the Body Snatchers

Air travel gets to be a worse experience for travelers with every passing year. Steadily and starkly rising prices and separately charging for each and every idea companies can come up with for getting more money. Airport security keeps getting more inconvenient procedures and passengers get less and less comfort and privacy. Kiosks and self-service machines for everything replacing human services. Luggage conveyor belts that drop your suitcase from a storey high and break it. Mandatory facial recognition systems as replacement for boarding passes that do not disclose what they do with your photo or how long they keep it once they take it.

When a bad novelty appears in other countries, some agency decides years later it’s time to bring it to Brazil, too.

The public consultation

The National Nuclear Energy Commission (CNEN in the Portuguese acronym) is the Brazilian government agency responsible for orientation, planning, supervision, and control of the Brazil’s nuclear program.

Last Monday, CNEN has opened a public consultation in favor of allowing and regulating the use for public security purposes of body scanners that use ionizing radiation.

Such machines have been used in the past in some countries, including the United States, not without much controversy around its lack of effectiveness, invasiveness and health hazards.

What are body scanners

Body scanning technology for security screening commonly use some sort of radiation that penetrates clothes and capture reflections upon the skin surface to generate a body image. As clothes are transparent to the radiation, the body images they generate are very similar to what the person would look like when nude.

The stated purpose of such equipment is to find items concealed beneath clothes, such as weapons. It is sometimes deployed in places where security screenings are required, such as airports.

Scanners usually resemble a small room or platform, where the person must stand in the designated spot in the center and are instructed to hold their arms up in the air for the duration of the procedure.

Types of scanners

Two major categories of body scanners have been deployed at airports: backscatter x-ray and millimeter wave scanners. The former utilizes ionizing radiation, the latter a type of microwave, non-ionizing radiation. The former builds a 2D image of the body, while the latter constructs a 3D image. Both pose different levels of health hazards and privacy concerns.

Less common than those are transmission x-ray scanners that use a higher dose of penetrating radiation that passes through the human body and is captured by an array of receptors. Like a medical x-ray, those scanners show inside the body, so they can show objects hidden in body cavities or that have been surgically implanted. They are alleged to have been deployed in Ghana and Nigeria and are official security screening policy in some prison systems. Because of the high dose of radiation, this type os scanner is also the one that offers the greatest health risk to the person being scanned. In this setup, the law usually requires that the cumulative annual dose applied to each subject be tracked and prohibit exposure above a certain limit.

There are also body scanners based on passively collecting infrared light emitted by body heat, which is blocked by concealed weapons beneath clothes. This type of scanner usually does not show off any intimate body parts and were apparently being tested in 2019 at a London rail station. Because this type of body scanner emits no radiation, it is generally considered safe of health concerns. They are similar to the thermal image cameras that have been used to try to detect fever in passengers in an attempt to deter the spread of Covid since 2020. Even though they have not been effective for that particular purpose, they could be a safer option for security screening, concerning health and privacy.

The CNEN proposal does not mention any of those types, but since it specifically regulates only equipment using ionizing radiation, we can only deduce that they intend either:

- to allow the old backscatter x-ray body scanners to come to Brazil,

- to allow the use of transmission x-ray body scanners in Brazil, or

- they are willing to let manufacturers use Brazil as a testing ground to experiment with new types of scanners using ionizing radiation,

or maybe all of the above. In any case, as we will see, scanners using ionizing radiation are clearly the ones posing the greatest health risks.

History in airports

Full-body scanners started being deployed in airport security screening in the United States and in Schiphol airport in the Netherlands in the late 2000’s. The alleged justification was a response to the Christmas 2009 attempted bombing of Northwest Airlines Flight 253, which fortunately was averted by passengers who fought back the perpetrator. As we’ll see, according to security experts, the willingness of passengers to fight back is one of the key factors that make flights more secure today.

While the US initially used the backscatter x-ray scanners branded Rapiscan, the Netherlands have used since the beginning millimeter wave scanners of the SafeView brand. The US later dropped the Rapiscan naked body scanners after the manufacturer failed to make them “less revealing” and has been ever since also using exclusively millimeter wave scanners. Those newer scanners also happen to have software that analyses the naked image automatically and creates a “paper figure” doll. Security agents allegedly see only those figures, which indicate places in the passenger body for further searches. However, as we’ll see, even that type of body scanner has seen its share of controversies.

Despite all controversies, the US has allegedly been supplying Ghana and Nigeria with see-through, high dosage x-ray full body scanners, that show inside the body just like a medical x-ray would. The ethics of the practice have been questioned by many, including the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU).

In some places, one can opt-out of a full-body scan (but reportedly not so in Australia) and receive a pat down instead. In the Netherlands, this is just a “normal”, unintrusive pat down. In the US, however, since 2010 people who opt-out of the machines receive an invasive “enhanced pat down” that have been described as akin to sexual assault, as they involve groping of intimate body parts by the security agent.

Ineffective and expensive

Renowned security expert Bruce Schneier often says that only two things have made flying more secure since 9/11: steel reinforced cockpit doors and teaching passengers that they should fight back. Many years have passed since airport security measures have ramped up, and observing the outcome of those measures, he states that current additional airport security procedures are a waste of time and money without providing added security. He affirms that the procedures should scale down to pre-9/11 levels. But why?

For once, he argues that many security measures are effective at stopping dumb attackers, but they are not as effective at stopping smart attackers:

The very rare smart terrorists are going to be able to bypass whatever we implement or choose an easier target. The more common stupid terrorists are going to be stopped by whatever measures we implement.

There has been ample evidence of the ineffectiveness of such security measures over the years.

Schneier coined in the term “security theater” for the practice of taking ineffective security measures, for the sole purpose of reassuring the public, rather than actually preventing or deterring real threats.

According to him, body scanners are one such example of security theater. Indeed, there have been several episodes of body scanning technology being thwarted and people being able to pass security checkpoints with concealed weapons. In November 2011 a group of researchers published a paper in the Journal of Transportation Security that

suggested terrorists might fool the Rapiscan machines and others like it employing the X-ray “backscatter” technique. A terrorist, the report found, could tape a thin film of explosives of about 15-20 centimeters in diameter to the stomach and walk through the machine undetected.

as reported by Wired magazine. Millimeter wave scanners are not in any way more effective. In 2012, computer scientist, civil rights attorney and blogger Jonathan Corbett published video that became viral that demonstrated the ineffectiveness of the machines by

showing how he was able to get a metal box through backscatter X-ray and millimeter wave scanners in two US airports. In April 2012, Corbett released a second video interviewing a TSA screener, who described firearms and simulated explosives passing through the scanners during internal testing and training.

In fact, CNN reported that the Transportation Security Administration – TSA had failed in detecting threats in screening tests 95% of the time. Schneier explains that

For those of us who have been watching the TSA, the 95% number wasn’t that much of a surprise. The TSA has been failing these sorts of tests since its inception: failures in 2003, a 91% failure rate at Newark Liberty International in 2006, a 75% failure rate at Los Angeles International in 2007, more failures in 2008. And those are just the public test results; I’m sure there are many more similarly damning reports the TSA has kept secret out of embarrassment.

Yet this is even more staggering when you consider that those scanners have cost US$ 150,000 per unit in 2008 (according to a report by Politico) which, when corrected by inflation to today’s values would be something like US$ 208,000. In Brazil’s currency, that would amount to well over a million BRL each. That’s a huge amount of money that, were CNEN to go forth with its proposal, would just be a huge waste of resources.

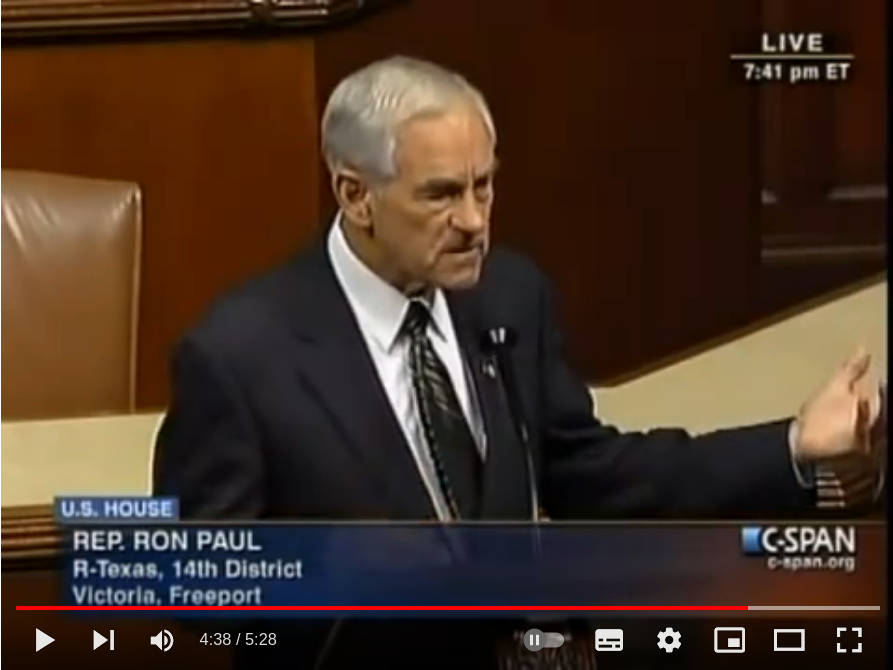

And where does all that wasted money go? In the US there has been at least one reported case of conflict of interest, where an individual who was responsible for the department procuring these machines was also having his private firm profit from them. The case was even reprehended by Senator Ron Paul (Rep.-TX) on the House floor:

Michael Chertoff! I mean, here’s the guy who was the head of the TSA, selling the equipment. And the equipment’s questionable. We don’t even know if it works, and it may well be dangerous to our health.

The push for adoption the technology has always been driven by corporate lobbyists. The sudden interest in bringing those machines to Brazil makes one wonder whose interests are behind the idea.

Recent events in Brazil have made many rethink the notion that the country used to be far away from concerns with terrorism that have permeated in the global north for the last 20 years. One might look at the threat and be tempted to justify the employment of body scanners in order to ramp up security and prevent threats such as the attempted bombing near Brasília International Airport on December 23rd, 2022, perpetrated by the same group who would a coupe of weeks later storm and ransack the capital’s seats of democratic institutions.

However, the attempt was carried out outside the airport premises and, as demonstrated above, even if perpetrated inside the airport, body scanners would not have been useful in preventing it anyway. So that case is definitely not a valid argument in favor of justifying bringing body scanners to Brazil.

Health concerns and types of radiation

As previously explained, the two most common body scanner types are backscatter x-ray scanners, which use ionizing radiation and millimeter wave scanners, that use non-ionizing radiation.

Ionizing radiation is a type of radiation that has enough energy to remove electrons from atoms and molecules, creating ions. This type of radiation includes gamma rays, x-rays, and ultraviolet light. Ionizing radiation can cause damage to living tissue, including DNA mutations and cancer. It is also used in medical treatments such as radiotherapy and in industrial processes.

Non-ionizing radiation, on the other hand, does not have enough energy to remove electrons from atoms or molecules. This type of radiation includes radio waves, microwaves, infrared light, and visible light. It does not cause the same kind of damage as ionizing radiation but can still be harmful if exposed to high levels for long periods of time. It can cause skin burns, eye damage, and other health problems. Non-ionizing radiation is used in many everyday applications such as cell phones, Wi-Fi networks, and television broadcasts.

The main difference between ionizing and non-ionizing radiation is the amount of energy they contain. Ionizing radiation has more energy than non-ionizing radiation and therefore poses a greater health risk. On the other hand, non-ionizing radiation does not have the same level of risk but can still be dangerous if exposed to high levels for long periods of time. In 2011, the World Health Organization (WHO) added radio frequency electromagnetic fields, including microwave and millimeter waves, such as those used in the body scanners but also in common equipment like cell phones and wifi routers, to their list of things which can potentially cause cancer on humans. The classification was done in context of assessing the potential health risks associated to frequent and extensive cell phone use, but applies to all radio frequency waves.

Ever since the US dropped backscatter x-ray body scanners from their airports, one could hardly see them used elsewhere in the world. Yet it is exactly that type of body scanners that CNEN intends to introduce in Brazil.

For exposure to ionizing radiation, the unit of measure is the Sievert. In the US, there is a the effective dose allowed for each exposition. Body scanners are not allowed be above 250 microsieverts. However, on the regulation CNEN proposes has no maximum allowed dosage at all.

Even considering that, there are reports on how the legal limits to ionizing radiation exposure have been breached, sometimes exhibiting even tenfold the expected radiation. So even if the CNEN was to set a limit in regulation, it would be difficult to ensure that that limit would always be respected.

Even if the limit were to be respected and verified, it’s important to note that, since backscatter x-ray body scanning technology concentrates energy on the body surface, rather than distributed throughout the whole body, the effective dose to the skin could be much higher. A number of researchers at the University of California, San Francisco, (UCSF) have argued in an open letter to the Assistant to the President for Science and Technology in April 2010:

The X-ray dose from these devices has often been compared in the media to the cosmic ray exposure inherent to airplane travel or that of a chest X-ray. However, this comparison is very misleading: both the air travel cosmic ray exposure and chest X- rays have much higher X-ray energies and the health consequences are appropriately understood in terms of the whole body volume dose. In contrast, these new airport scanners are largely depositing their energy into the skin and immediately adjacent tissue, and since this is such a small fraction of body weight/vol, possibly by one to two orders of magnitude, the real dose to the skin is now high.

They were also concerned with possible malfunctions in the equipment causing spikes of energy dose that could be harmful to the human skin:

Because this device can scan a human in a few seconds, the X-ray beam is very intense. Any glitch in power at any point in the hardware (or more importantly in software) that stops the device could cause an intense radiation dose to a single spot on the skin.

If backscatter x-ray body scanner technology safety is often brought into question, it doesn’t mean that the other type of body scanning technology is safe.

Millimeter wave scanners emit non-ionizing radiation in the millimeter wavelength band, which is a subset of the microwave radio frequency (RF) spectrum. Microwaves affect water molecules and, depending on the energy density, it could heat skin and eye tissues and potentially cause burns. While a 2001 study found no evidence of 94 GHz RF in skin carcinogenesis in animals, a 2009 study funded by National Institute of Health, conducted by U.S. Department of Energy’s Los Alamos National Laboratories Theoretical Division and Center for Nonlinear Studies and Harvard University Medical School found that

a specific terahertz radiation exposure may significantly affect the natural dynamics of DNA, and thereby influence intricate molecular processes involved in gene expression and DNA replication.

Millimiter waves are also present in WiGig, also known as 60 GHz Wi-Fi. A recent study found out that 60 GHz millimeter waves could cause eye injury.

Privacy concerns and data leaks

Using a full-body scanner has been compared by security experts as akin to a strip-search. It can be described as

a virtual strip search that reveals not only our private body parts, but also intimate medical details like colostomy bags.

It can also be especially embarrassing to people who need to use prosthetics and provoke discrimination against transgender people.

The UK Equality and Human Rights Commission argued in 2010 that full-body scanners were a risk to human rights and might be breaking the law. As even children are subjected to the procedure, a UK court has decided that body scanning of children violates UK laws against child pornography:

The decision followed a warning from Terri Dowty, of Action for Rights of Children, that the scanners could breach the Protection of Children Act 1978, under which it is illegal to create an indecent image or a “pseudo-image” of a child.

There is also a concern regarding storage and possible leaks of images. The ACLU has argued that

the machine constitutes an invasion of privacy as it can display graphic images of nude bodies and its use could pave the way to widespread abuse of the images taken, with some possibly being posted or traded on the internet.

In 2012, the TSA decided to dump the Rapiscan machines after OSI Systems had allegedly failed to make them “less revealing”. They instated new body scanners in their place that instead of naked body image, would supposedly only display on screen a processed doll figure model, indicating body parts for further screening. Despiting insisting that the scanners do not store the original naked images generated by the devices, a TSA procurement document obtained through a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request by the Electronic Privacy Information Center has revealed that they do require that body scanner manufacturers provide the functions to store and transmit those images. It was later found that the machines did record and store full body scan images. In response to that, TSA claimed it was only used

for “testing, training, and evaluation purposes.” However, the TSA also admitted that there’s nothing preventing this “test mode” from being turned on while in regular use.

Yet, despite those claims, Politico has reported that a former TSA agent confessed that yes, the scanner didn’t work, but did let see you naked:

We quickly found out the trainer was not kidding: Officers discovered that the machines were good at detecting just about everything besides cleverly hidden explosives and guns. The only thing more absurd than how poorly the full-body scanners performed was the incredible amount of time the machines wasted for everyone.

To add insult to injury, some agents would, according to the report, even look and laugh at seeing people naked:

Many of the images we gawked at were of overweight people, their every fold and dimple on full awful display. Piercings of every kind were visible. Women who’d had mastectomies were easy to discern—their chests showed up on our screens as dull, pixelated regions. Hernias appeared as bulging, blistery growths in the crotch area.

In 2010, Gizmodo investigated the use of body scanners by the US Marshals Service and obtained, through a FOIA request, a sample of 100 images sample out of the 35,000 naked body images they had obtained through the machine and stored. This has been reported as evidence that the machines installed in airports and public buildings are indeed capable of storing the original images. If the images are stored, there always is a risk of them leaking and exposing the people that have been subjected to it.

Categories of scanners proposed by CNEN

The backscatter x-ray type of body scanner uses x-rays, a form of ionizing radiation that has known effects on human cells and increase the risk of developing cancer. The type of body scanner that CNEN intends to allow is the one that operates with ionizing radiation. On the public consultation they are divided in two categories:

- general usage systems, for equipment that expose people to a dose of ionizing radiation of up to 0.1 µSv per inspection

- limited usage systems, for equipment that expose people to a dose of ionizing radiation above 0.1 µSv per inspection

The difference between these two categories is that, in “general usage systems”, only individuals from the public who have given explicit written consent can be screened. For “limited usage systems”, however, besides having a higher dosage of ionizing radiation, no such consent is required. The bylaw would also require operators in the latter case to keep track of the annual dosage those people are subjected to.

Those provisions may mean that the first type of system would be deployed to the general public, while the second is meant for the prison system, but that is just mere speculation.

A nonsensical proposal

To sum it up, the type of body scanner technology the CNEN is proposing is expensive, ineffective, poses serious health risks, invades on people’s bodily privacy and have been abandoned by the United States and Europe for more than a decade long. It makes no sense at all to propose to bring them to Brazil at this time.

Makes one wonder who is lobbying CNEN in favor of this thing and how much they have to gain once this expensive and ineffective technology is procured.

What can I do to stop it?

Raise awareness, tell your friends, colleagues and acquaintances, share on social media, mention all of the problems and dangers of body scanners.

It’s also important to leave comments on the public consultation making it clear that using those devices in Brazil is not acceptable and articulate the reasons why. This article contains plenty of explanations and references that can be grounds for immediately rejecting this unreasonable proposal. The consultation is open until this Sunday, April 19th, 2023.

Edited (2023-03-15): corrected the date of the consultation, as it ends in April, not March, as I had written before.