Update on Senacon's decision on Meta's data sharing

Almost a month ago I wrote about how Senacon, which is the National Secretariat for Consumer Defense in Brazil, saw no harm in WhatsApp’s new metadata sharing practices announced by Meta last year.

Now, thanks to a Access to Information Law request made by data journalism-focused news agency Fiquem Sabendo, we learn more about the alleged reasons behind the decision. In response, they’ve obtained access to Technical Note no. 42/2022/CGCTSA/DPDC/SENACON/MJ, which is about

Preliminar ascertainment for supposed violations of consumer rights related to the sharing of personal data from WhatsApp to the Facebook Inc group of companies in violation of the Brazilian Civil Rights Framework for the Internet and Consumer Protection Code. Request for clarification by this Department of Consumer Defence and Protection. Information provided by the ascertained. Absence of violation to consumer legislation. Suggestion of closure.

The main alleged reasons for dismissing the case are:

- WhatsApp already did offer an opt-out choice for consumers to choose not to share their data with the Meta group;

- the company claims that the personal messages are end-to-end encrypted for all WhatsApp users, even those who did not op-out in 2016;

- the lack of evidence in the case for data leaks by WhatsApp/Facebook;

- a similar case has also been dismissed by the National Personal Data Protection Agency – ANPD, which supposedly had found no violation of privacy in the new privacy policy and found it adequate to Brazilian Data Protection Law – LGPD, as expressed in Technical Note n. 49/2022/CGF/ANPD.

Next we’re going to explore why none of those reasons hold their ground.

Argument no. 1: the supposed Opt-out and the No-way-out of WhatsApp

It is true that WhatsApp has once offered an opt-out option for users who didn’t want their data to be shared with the other companies. However, the last time that that happened was in 2016 and the option hasn’t been available since. As reported by G1:

The last time WhatsApp has made a significant change to their privacy policy was in 2016, but people who already had been using the app could deny sharing the data with Facebook. New accounts, on the other hand, had no such option.

This means that anyone who started using WhatsApp after that day has never been offered the option not to share their data. For Senacon, then, don’t those people matter?

Perhaps one could argue that they should not be accepting the terms and using WhatsApp in the first place. There are secure, free and open source messaging apps that are not owned by a tech giant. I even recommend using them: as I wrote in the last article, Element and Signal are excellent apps.

But how practical is that, given that pretty much every social and commercial relationship in this country is mediated by WhatsApp? If you want to use Element or Signal, you can try convincing your family, friends and colleagues to use it too, and a few might even try it. But good lock trying to order something at the local bakery, pharmacy or calling a plumber when you need service. Some companies you must relate to often don’t have an email, but they surely do offer customer service through WhatsApp. Even some government services are offered there. Is there really a choice, in practice, for a Brazilian to deny the terms of service and not use the service?

Argument no. 2: end-to-end encryption of what?

Surely Meta claims that the contents of messages are end-to-end encrypted. One either needs to believe their claim or not. As the app is closed source, it is completely impossible to verify the veracity of that claim.

Still, even if it is true, only the contents of messages are encrypted and Meta can’t access them. Metadata, such as who you talk to, their contact numbers, when and how often do you exchange messages with each other, etc., are still perfectly visible to Meta and they indeed want it so much as to demand that you share it with its corporate relatives. For companies like Facebook, that have micro targeted advertising as their main business model, such data is invaluable.

As we learn from every security expert, metadata is as much important to privacy, if not more, than the data itself. So the excuse that the company does not have access to the contents of messages has nothing to do with the issue at hand and is no argument with which to dismiss the complaint.

Argument no. 3: if it’s not shoved in my face, it doesn’t exist

The third argument is that the case files do not present evidence of data leaks from Meta. I do not even need to spend much effort to explain this could only be considered willful ignorance. Anyone who’s been following the news or do a web search will quickly find out about the Facebook Cambridge Analytica scandal disclosed in 2018, which had Mark Zuckerberg having to testify in the United States Congress, or the half a billion Facebook users data leak in April 2021.

Argument no. 4: let’s claim that another report says what it doesn’t say

Now this is interesting. The fact that a case against Meta has already been concluded this year by the ANPD was not known to me and did not receive as much media attention as when the controversy started in 2021.

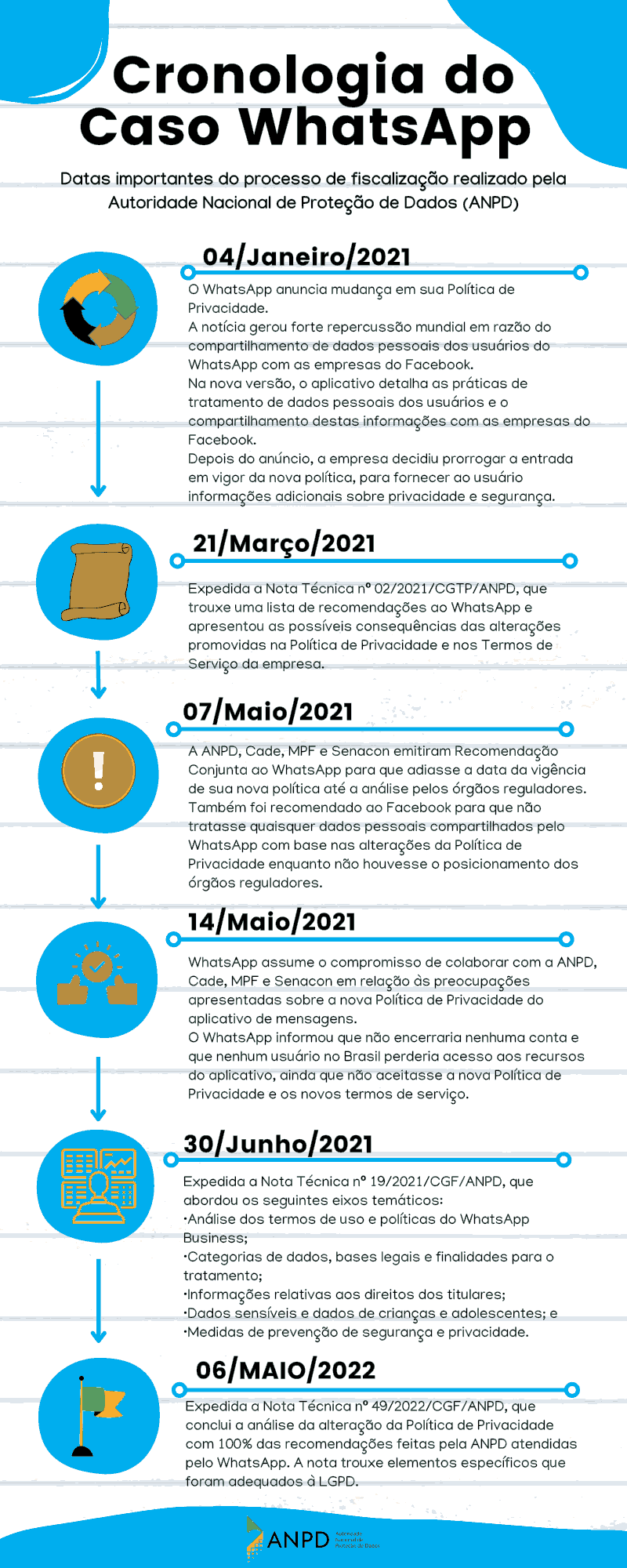

ANPD’s site even has a press release explaining the case and features an infographic-like timeline of events starting with the terms of service change in January 2021.

Furthermore, they have even made available the contents of the joint recommendation and the three technical notes expedited by ANPD about the case:

- Act of Joint Recommendation (ANPD, Cade, MPF and Senacon)

- Technical Note n. 02/2021/CGTP/ANPD

- Technical Note n. 19/2021/CGF/ANPD

- Technical Note n. 49/2022/CGF/ANPD

I have yet to read them all through, and the analysis of those documents might warrant a dedicated post. I can already say that the last technical note did recognize that Meta did comply with the agency’s demands, but still determined that a new procedure should be open in order to ascertain the compliance of the company’s data sharing practices to the LGPD.

7.1.4. A new procedure should be instantiated specifically to evaluate the data sharing practices between WhatsApp and the companies in the Facebook (Meta) group, in order to ascertain its compliance to the terms of the LGPD.

So it is a completely false statement when Senacon claims that the ANPD has already found the practices to be LGPD compliant:

2.4. One can also notice that the most recent updates to the Terms of Service and Privacy Policy were the subject of analysis by the ANPD, which, after analyzing the versions of the Privacy Policy from all of the tools from the app WhatsApp (WhatsApp Messenger, WhatsApp for Business and WhatsApp for Business - API), has concluded for their compliance to the LGPD, through the 3rd Technical Note no. 49/2022/CGF/ANPD, issued in 06 May 2022.

Furthermore, ANPD has been considering only LGPD compliance, which is its own role in the matter. Senacon, on the other hand, was supposed to verify compliance with consumer protection law and regulations – an entirely different matter – and Senacon’s technical note has no consideration on that front. In fact, it does not even cite any consumer regulation, except for stating the complaint itself on the first paragraph. The fact that ANPD recognized that Meta has complied with its demands in regards to WhatsApp’s terms of service is a non sequitur to Senacon’s conclusion.

Is there a way out?

All things considered, we’re still left with the problem of a society taken hostage by Meta. The few occasions where millions of people actually have decided to install another messenger app were those when the judiciary inconsequentially blocked it nation wide in retaliation for non-compliance due to the mistaken conception that it would be possible for the company to hand over the contents of end-to-end encrypted messages exchanged between criminals. If those judges had any technical advisory they should have asked that WhatsApp handle the metadata instead – which could arguably have been sufficient, when combined with other means of obtaining evidence, to prove the case against any given criminal.

During those WhatsApp blackouts, millions of Brazilians installed Telegram and other messaging apps. But as soon as WhatsApp is back online, those people uninstalled those apps and went back to using what they were used to – WhatsApp.

I also bears mention once more that the utter dominance of WhatsApp in the Brazilian market is also the consequence of the practice of zero rating – when the company abuses its economic power by bribing the mobile internet companies to keep its apps out of strict data traffic regimes that is their business model. To the blind and complicit eye of government entities such as Cade and Anatel, who since 2018 have institutionalized zero rating despite the net neutrality determined by the Brazilian Civil Rights Framework for the Internet.

Had WhatsApp been blocked this time for an actually justifiable reason instead, maybe it could have been just the push for the network effects, combined by the hay fire public consciousness about shady metadata sharing practices used by many companies, to kick in and create some actual competition and diversity in the messaging apps landscape.