Remembering Therezinha Costa

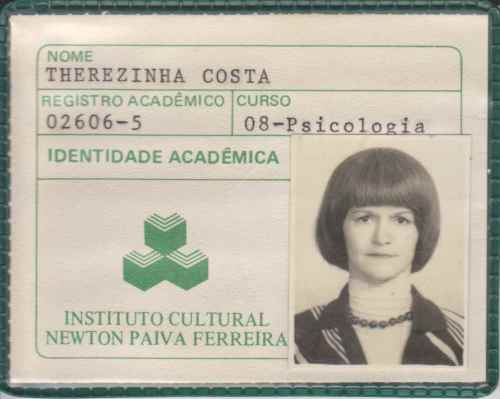

Therezinha Costa was born in Teixeiras, Minas Gerais, Brazil in August 13th, 19XX (I won’t say the exact year, later you will find out why), daughter of Maria Luiza Costa and Antônio Domingos Costa, the youngest among 8 siblings. Aunt Terô, as we affectionately called her, was my grandmother Ana Luiza’s sister. She was a smart, kind, and caring person, very dear to everyone in the family. We used to turn to her for counsel in many situations in life. She had a talent for helping us understand ourselves better. In the words of my aunt Ana Lúcia, who is her niece,

Tia Therezinha was a natural born psychologist! Se helped me a lot in situations with many emotional and existential conflicts. She was also in many respects a mother, such as in her attention, and out relationship stood very much in equal footing. That was very important to me!

That may have been one of the reasons why she decided to study psychology, even at a relatively late age, and despite the many obstacles she had to face in going to the university.

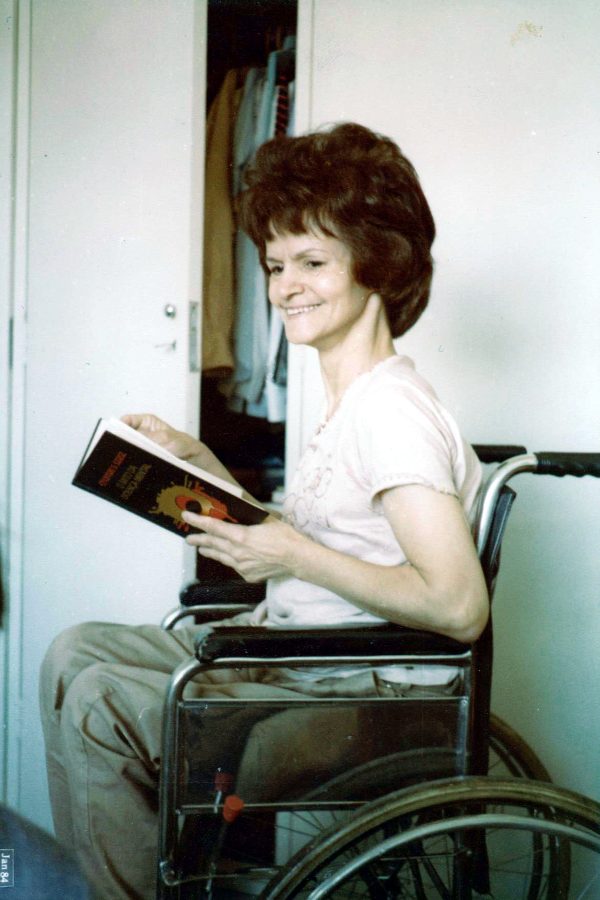

At the age of 9, she was afflicted with polio, which left her paralyzed from the waist below. Despite her condition, she was a very active and independent person and did most things herself. For example, in order to reach something high on a shelf, she would often sit on the arms of the wheelchair for support and get the thing. In situations she did need help, however, it was very easy for others to do it because she kept herself a very light body. Even so, the lack of accessibility then still made life more difficult. In the 1980s in Brazil, almost no buildings were accessible to people with reduced mobility. I remember my father telling me that the faculty she went to did not have an entrance ramp and she had to be carried up a long staircase in order to be able to access her faculty classes. It’s a good thing the laws have changed since then and every building is required to have access ramps or elevators. She would also sometimes having difficulty in finding a taxi willing to take her along with the wheelchair.

As a kid, I enjoyed having long conversations with her at any time about any subject. Sometimes, we talked at bedtime in the dark for what felt to me like hours in my perception of a child, but that was most likely around a half hour long. I remember we played many board and puzzle games together, such as “Detetive” (a deduction board game manufactured by Estrela, similar to Cluedo / Clue), “Cara a Cara” (Guess Who), “Resta Um” (Peg solitaire), “Cilada” (Gridlock), the Rubik’s Cube and a world traveling board game whose name I do not recall, and many others. She was especially fond of the Cup and Ball dexterity game, which I liked too. In this game, the player holds a stick with a pin, which is connected by a string to a ball. The player must move the stick to throw the ball into the air, and then fit the pin in the small cavity in the ball.

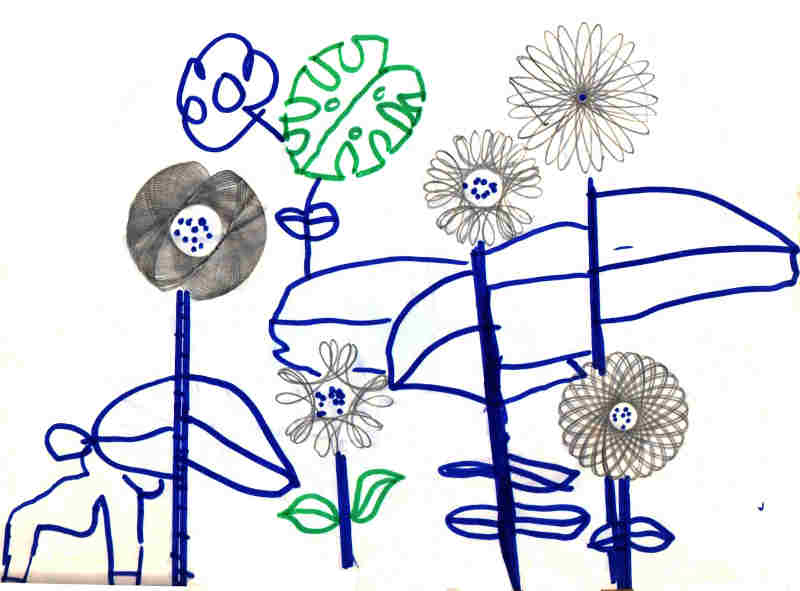

We also liked to draw together beautiful curves made with the Spirograph, which I got as a present from her, or from my father, I do not remember. If you don’t know what a spirograph is or the mesmerizing drawings it enables us to do, think of a circle inside another tethered circle, connected by teeth (like a cog), and with holes inside it for inserting a pen or pencil. When the wheel turns, a curve appears. The shape of the curve depends on many parameters, such as which hole you use or the size of the inner wheel. Check out the Wikipedia page for more information, or the animation below.

Those figures always got me thinking about whether or not the curve would connect again at the beginning and, if so, how many turns of the wheel it would take. I’m positive that all those puzzles and logic games have influenced me and made me love mathematics.

When I was very young, I once took a cooled down piece of coal from the fireplace and wrote “EAT” on it. My father initially thought I was hungry for the word it formed in English, considering that I had started writing at a quite young age, but then realized it was meant for the initials of our names: Eduardo, Augusto, Therezinha.

Aunt Terô made the best pão de queijo (or Brazilian cheese roll, a traditional and popular snack in state of Minas Gerais) I have ever had the pleasure of eating. In her recipe, later also reproduced by my father for many years, as I remember, took:

- Cassava starch (of the “sweet”, not “sour” variety)

- eggs

- butter

- milk

- Canastra cheese

Because I was a child, I do not remember or know the quantities used. She, and later my father, would be very stringent in the rule that “sour” cassava starch was never to be used and no cheese other than Canastra cheese should go in the making of our pão de queijo. Canastra cheese is a special type of cheese made in the Canastra Mountain Range region of the state of Minas Gerais, in Brazil.

I have found a version of a recipe (in Portuguese), that uses Canastra cheese. That recipe rather regrettably also takes “sour” cassava starch 😬 besides the “sweet” one. Just kidding, mixing the starch types is common practice and is not bad: the “sweet” variety gives it ligature and elasticity; the acidic nature of the “sour” favors fermentation more and makes it grow.

Pão de queijo

(recipe attributed to Mario)

- 200 g cassava starch, sour type

- 200 g cassava starch, sweet type

- 300 g artisanal Canastra cheese, half ripe

- 100 g unsalted butter

- 300 g whole milk

- 100 ml water

- 15 g salt

- 4 eggs

- In a large bowl, mix both starch types and the salt. In a small pan, boil the water, milk and butter together. When they boil, mix with a spoon and pour slowly all the liquid over the powder. Mix slowly with a spoon and after it cools down also with your fingers.

- Grate the cheese thick and add it along with the eggs. Mix everything and knead the dough with the palms of your hands until the small blobs of starch are gone, leaving only the pieces of cheese.

- Grease your hands with a drop of oil and roll the dough into small balls (20 g each). Grease the baking tray or cover it in aluminium foil and lay the pães de queijo set apart 3 cm from each other.

- Heat the oven to 180°C and bake them to your point of preference.

Aunt Therezinha’s pão de queijo was most delicious. Sometimes I would offer help in kneading the dough. However, as a child, I was too impatient to wait the 30 minutes it takes to make in the oven. Once I even tasted a tiny piece of it raw, despite it being ill advised by adults, because the dough contains raw eggs, which carries the risk of contamination. As Aunt Terô would say: “the hasty have it raw”.

One of the last photos of her was taken by me with my Kodak I77XF Instamatic Camera, which I used as much as my parents would give me film for. Yes, cameras at the time were only capable of taking photos when they had film, which would then need to be taking to a studio and be developed. Despite what the name might suggest, unlike a Polaroid camera, the camera does not print out any photos instantly. It takes 126 Kodak film and takes pictures in the quite unusual square aspect ratio. One could say that Kodak made square aspect ratio photos popular decades before Instagram did. That photo would then be featured in the editorial of a “magazine” I did, written in a typewriter.

The idea of the magazine I did as a child was to photocopy articles from books and encyclopedias about subjects I found interesting, then distribute it to family members. I asked Aunt Terô for her opinion on what the subject of the second issue should be, and she suggested chemistry. The issue is dated August 15th, 1990.

A translation follows:

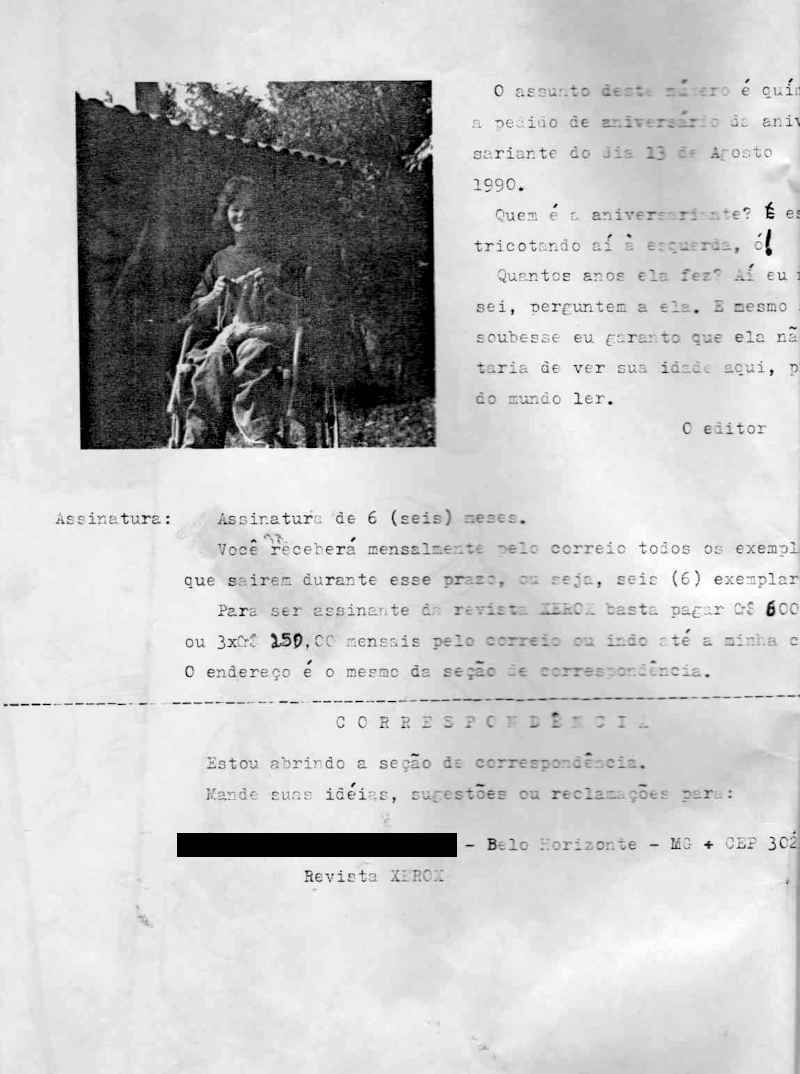

The subject of this issue is chemistry, at request from the person celebrating her birthday on August 13th, 1990.

Who is having a birthday? She’s the one knitting there, to the left, look.

How old is she? That, I do not know, ask her. And even if I knew I can guarantee she would not like everyone to see her age here, for everyone to read.

The editor.

Looking at it today, the lack of spelling errors and playful tone of this editorial have caught my attention. This passage above is the reason why I have omitted her year of birth at the beginning of this text.

She loved to knit. I remember having gloves, caps, and other clothes knitted by her when I was a child. To this day I have a bed sheet made by her.

Soon after that, in November 1990, a tragic car accident took her life and her sister’s Ana Luiza, who was my grandmother. My grandfather was also gravely injured, but after a long hospital stay he recovered himself. They all still live in our hearts and my childhood memories of the time I spent with them are very dear to me.