My first ever Python code, 14 years later

While browsing some old backups of mine I serendipitously came across the first ever pieces of code I wrote in Python. It was back in 2007, while I was an undergrad in Computational Mathematics, when I studied the fundamentals of cryptography in college with professor Dr. Jeroen van de Graaf at the Computer Science Department of the Federal University of Minas Gerais. For the learning exercises, we needed to make calculations with large integers, which was not something simple to do in many programming languages at the time. Professor Jeroen suggested that we use Python for that, and it turned out to be very easy to translate the abstract algorithms from the books into running code.

We used many books on number theory and cryptography, but the one we recurred to most often was the “Handbook of Applied Cryptography”, by Menezes, Oorschot and Vanstone, often mentioned by the acronym “HAC”. Many of the algorithms we implemented in the course were described in that book.

The state of Python was quite different at the time, as the language has

evolved a lot over the years. I think I used Python version 2.3. Back

then, using the division operator / on integers would return integers.

Now you get a float instead. So in Python 3 you have to use the double

slash // for integer division if you want the result to be an int.

Furthermore, my own inexperience with the language is evident in the code

there. It is obviously apparent that I’m trying to imitate some C

language structures in several places. For example, I used a for loop

exactly like one would do in C, which is what I was used to at the time,

instead of iterating on a list.

for i in range(0 , t) :

a = numbers[i]

# instead of the pythonic

for a in numbers[:t]:

...

On the other hand, it brings a smile to my face to see a header in that file specifying the GPL 2 license for the code. My admiration for and commitment to the free and open source software idea comes a long way.

So, what did I implement there? I’m not sure exactly which one I made first, because the file modification timestamps are wrong – they were updated in a previous backup operation, but it’s for sure one of those. The code below tries to implement the Miller-Rabin algorithm for determining whether a number is composite or likely to be prime. I’m not going to show the original code as it is implemented completely wrong. Miller-Rabin is a probabilistic test, so it begins with the choice of a random number \(a\), where \(2 \leq a \leq n - 2\). In the exercise, I had used a fixed list of numbers instead. And that is just one of many mistakes.

If you are curious as to how the Miller-Rabin test works, here is a (hopefully) fixed version of my implementation of the algorithm described in Chapter 4 of HAC:

from random import randint

from colorama import Fore

def is_prime_MR (n: int, t: int) -> bool:

"""Checks whether a number is composite or likely to be prime using

the Miller-Rabin probabilistic test.

:param int n: The integer to be tested

:param int t: Security parameter, large numbers take longer but

increase the probability of being prime

:return: False if the number is composite, True if prime or pseudoprime

:rtype: bool

"""

if (n % 2 == 0) : return False

r = n - 1

s = 0

while (r % 2 == 0):

s = s + 1

r = r // 2

for i in range(t):

a = randint(2, n - 2)

y = pow (a, r, n)

if (y != 1) and (y != n - 1):

j = 1

while (j < s) and (y != n - 1):

y = (y * y) % n

if y == 1:

return False

j = j + 1

if y != n - 1:

return False

return True

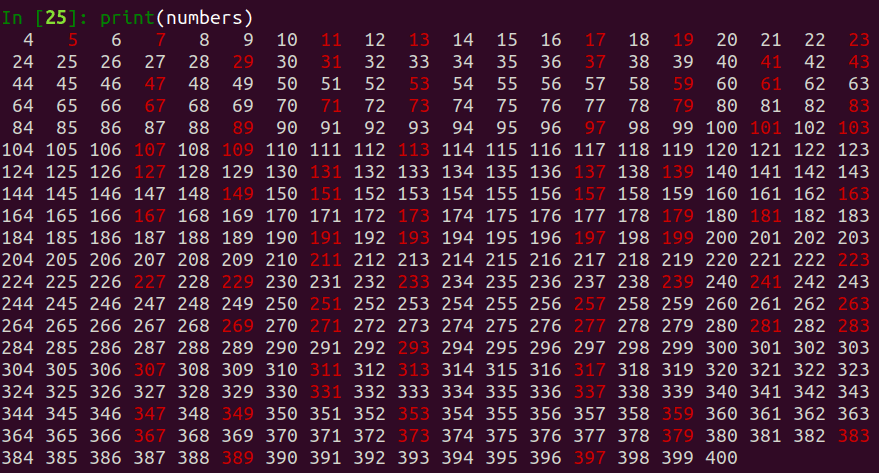

# test numbers from 4 to 400 with 10,000 iterations each

numbers = ' '.join(

(Fore.RED if is_prime_MR(n, 10000) else Fore.WHITE) + f'{n:3}'

for n in range(4, 401)

)

I also implemented the Pollard Rho algorithms for factorization and for finding discrete logarithms, as described in HAC, Chapter 3. One could immediately spot the extensive use of lambda functions, which is interesting because:

- it helps a lot in implementing math algorithms such as this, and

- they were already present there this early in Python’s history.

For the greatest common divisor we used the contemporary version of numbthy.py by Robert Campbell, which is simple and useful for learning, but nowadays one would probably prefer importing numpy’s gdc which is calculated in C and would perform better. However, even with a modern day computer I still could not find any factor of the composite number 8834884587090814646372459890377418962766907 after an hour of calculations. Maybe so if I had taken the effort to paralelize the algorithm to benefit from today’s multi-core CPUs, which I didn’t. For the smaller number 618240007109027021 though, it finds the factor 250387201 almost immediately. The code below was updated to Python 3, and I advise you against using it as it may still contain errors. However, if you must, then please proceed with caution:

from numpy import gcd

def prho_factor (n: int) -> int:

"""Factors a composite number n that is not a power of a prime number.

:param int n: A composite number n

:returns: A non-trivial factor d of n

"""

a = b = 2

while True:

g = lambda x : (x * x + 1) % n

a, b = g(a), g(g(b))

d = gcd (a - b, n)

if (d > 1) and (d < n):

return d

if d == n:

break

Overall it was very interesting to revisit both these algorithms from number theory and witness again the beginning my personal journey in learning Python. According to the metadata in an OpenDocument text, this code is just now completing its 14 anniversary. 🎂 Yay!

This means that this marks the beginning of my 15th year with Python. And still every day I learn something new. I can only anticipate the joy of learning more Python on the next.