Why do we still call Facebook a platform? What is a platform, really?

With the tech giants under more scrutiny than ever, we keep hearing the media call the platform vs. publisher discussion repeatedly by the international press and also by US politicians. As the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) correctly puts it, for the purposes of CDA Section 230, it doesn’t matter. As EFF and other digital society thinkers have argued over the years CDA 230 makes no such distinction.

A question of semantics

But what is a “platform”, really? A common use among people outside the field of technology is to use the word to mean just a place that people can express themselves. If you have any website that accepts user-generated content, then you are a platform.

One problem with this definition is that almost everything that exists today would be considered a platform. A messenger service? A platform. An email server? Also a platform. The comment section of a blog? Platform it is.

Another problem is if you make an analogy of this definition to the analog world, many things that people wouldn’t normally consider to be a platform are suddenly platforms, too. People can talk to each other at the town square (or could, before the coronavirus). So it is a platform. A bulletin board. An art gallery. Walls with graffiti. Any form of expression. Almost everything is a platform. It is a mess.

So, maybe we should instead turn to the dictionary to try and find out a more restrictive meaning for the word platform.

For Oxford Learner’s Dictionary, in the context of computing, a platform simply means

the type of computer system or the software that is used.

For Merriam-Webster, in this context it means

the computer architecture and equipment using a particular operating system.

Dictionary.com delves into a bit further detail:

a major piece of software, as an operating system, an operating environment, or a database, under which various smaller application programs can be designed to run.

Examples of use of the word in this sense are when people say that a piece of software runs on a Windows platform, or a MacOS platform. But what about online services?

Online platforms

Similar to other kinds of software, online services are platforms when they do enable other kinds of software applications and services to run on top of it. Adrian Bridgwater’s piece for Forbes in 2015 brings the definition of the word platform closer to that concept:

Where we used to think of a platform as the underlying computer system, we now probably have to accept the fact that the industry considers a platform to be anything that you can build upon. To be clearer, a platform could be your smartphone i.e. it has its own device form factor and its own ability to interconnect with other software streams, therefore it’s a platform that you can do other things with that were not originally envisaged at the time of its initial design.

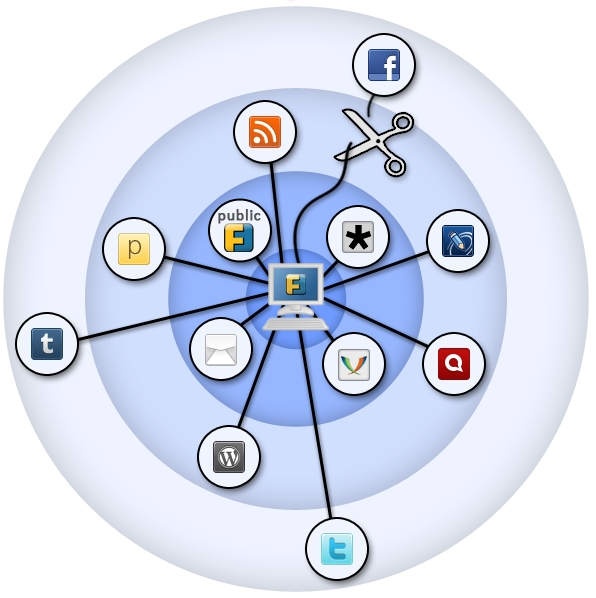

That might have been the case, as he argues, in 2015, for Facebook. However, if Facebook was once something that would could build upon by using extensive APIs to build new services, that possibility has certainly been cut off, in practice, in more recent years.

Facebook has been very aggressive in fighting other services that dare to let you connect to friends on Facebook and get content from Facebook without you actually getting into Facebook.

In 2008, a company called Power Ventures created a product that would do just that, letting users aggregate content from all of their social network accounts in a single place. Facebook not only blocked the application, but also went to court using the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA) of 1986, the same law that would be used years later to charge Aaron Swartz with penalties for up to thirty-five years in prison for downloading a batch of publicly-funded scientific articles his university was entitled to.

The legal battle took over nine years, and the courts have ordered the defendants to pay over a hundred thousand dollars and set a dangerous precedent that, due to the CFAA, a violation of Facebook’s terms of service could face CFAA charges. In the words of Andrew Crocker and Cory Doctorow for the EFF about the case,

even though the Ninth Circuit had previously decided that a violation of terms of service alone was not a CFAA violation, the court found that Power Ventures did violate the CFAA when it continued to provide its services after receiving the cease and desist letter. So the Power Ventures decision allows platforms to not only police their platforms against any terms of service violations they deem objectionable, but to turn even minor transgressions against a one-sided contract of adhesion into a violation of federal law that carries potentially serious civil and criminal liability.

More recently, the Ninth Circuit limited the scope of Power Ventures somewhat in HiQ v. LinkedIn. The court clarified that scraping public websites cannot be a CFAA violation regardless of personalized cease and desist letters sent to scrapers. However, that still leaves any material you have to log in to see—like most posts on Facebook—off limits to scraping if the platform decides it doesn’t like the scraper.

Another project that used to make possible the interoperability with several social networks is the free and open source software tool Friendica. It used to work with Facebook, until in 2015 Facebook cut off the API access which made possible that integration. In the words of Friendica enthusiast Andreas Hannusch in an interview for the Green Net Project, in 2018:

a great advantage is the ease of installation and the wide range of contact types I can communicate with: email, Friendica and related networks, even Twitter can be integrated. Facebook has stopped working since Facebook discontinued its API.

A third example is told by Jay Graber, developer and founder of Happening at the panel “If Big Tech is toxic, how do we build something better” held by the Internet Archive. She had once built a tool allowing for people to set up events and invite their friends in Facebook, using the Facebook API. However, Facebook only allows the application to see what friends are on your friends list if those friends have also previously authorized the same application to contact them. While this does serve Facebook to reduce liability in case an application decides to spam users, it also does stifle potential competitors from interoperating with Facebook’s user base in a way that would benefit those users.

Can this mess be fixed?

All things considered, the possibility to interoperate with Facebook has dwindled steadily over the years, to a point one could argue that Facebook is no longer a platform in the sense we have been discussing here.

I mean the kind of interoperability that does benefit the service’s users and are not necessarily what Facebook’s shareholders believe to be the most profitable. That’s the kind of interoperability that Facebook took advantage of to grow, when they used a tool to let users stay in touch with their friends who were still only using MySpace, but then kicked the ladder they used to climb to the top. It’s the concept Cory Doctorow calls adversarial interoperability (which is being re-branded as competitive compatibility because, according to Cory, Germans can’t pronounce it), in which new entrants to a market are allowed to interoperate with the established services of the dominant players, even if it is not in the interest of those players.

To improve the competitiveness in the tech sector, the CFAA, the [DMCA 1201(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anti-circumvention#United_States)] and other regulations that have favoured building giant effective monopolies is what needs fixing, not CDA 230.

The CDA 230, and its existing counterparts in other countries (such as article 19 of Marco Civil da Internet in Brazil) is what allows small sites that allow user content, like a Discourse forum that I run to actually be able to operate, since the responsibility for potentially illegal speech lies on the party actually speaking, and not the operator of the site. For these and many other reasons, as the EFF puts it, CDA 230 is actually good.

New regulation approaches have also to be considered very carefully, as the tech giants have a lot more resource to invest in compliance with it, while small startups and potential competitors often don’t. Because of this, Big Tech tends to see new regulations in favorable light, as they see it as a way to strengthen their monopolies, keeping new entrants away from the market. They also invest large quantities of money in lobbying for new regulation that favors them.

Another question we ought to be asking is: do we really need platforms at all? Mike Masnick from Techdirt proposes a different kind of solution on his essay Protocols, not Platforms, published by Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University.

A very interesting example of an open, decentralized protocol is the Matrix protocol for messaging and chat. There are many service nodes that use a bunch of different free and open source clients, such as element.io, that can seamlessly interoperate with each other.

Decentralizing services is a necessary step in solving the tech monopolies conundrum, but not a sufficient one. We’re still left with the question of content moderation, which is a problem when it’s centralized and difficult when it’s decentralized. A couple of recent Techdirt podcast episodes ( ”Making A Better Internet”, which was an online event by the Internet Archive, also available in video, and also “A More Competitive Web” ) do discuss some possible ideas to handle the problem. They are also excellent discussions in their own right with some of the best experts about internet policy and digital society. I highly recommend listening to them both. I also recommend the “How to fix the internet” podcast by the EFF.